On the edge of the fjord, the twin towers of Oslo City Hall rise like a red brick temple, stoic, as if poised on the water. Conceived in 1906 and completed in 1950, after decades of design and construction marked by wars, this building is both an emblem of Scandinavian sobriety and a remarkable showcase of art.

Designed by Arnstein Arneberg and Magnus Poulsson, the Rådhus embodies functionalism, the architectural spirit that prioritizes utility and clarity. Yet, far from being limited to pure austerity, the building refers to ancestral Norwegian traditions through its expressive, antique-looking bricks—large and rough, like those of the Middle Ages—and through the numerous works of art that tell the history of the country and the city.

Designed by Arnstein Arneberg and Magnus Poulsson, the Rådhus embodies functionalism, the architectural spirit that prioritizes utility and clarity. Yet, far from being limited to pure austerity, the building refers to ancestral Norwegian traditions through its expressive, antique-looking bricks—large and rough, like those of the Middle Ages—and through the numerous works of art that tell the history of the country and the city.

The project dates back to 1906: the idea of a modern town hall on Pipervika, facing the fjord, was first proposed. It wasn’t until competitions in 1915 and then 1918 that Arneberg and Poulsson were chosen from among 44 candidates. The actual construction began in the 1930s with a heavily revised project, influenced by the emerging functionalist style, including the addition of the two large, massive towers that give the building its strength. Construction was interrupted by the German Occupation. It wasn’t until 1950 that the Rådhus was finally inaugurated; this year, it celebrates its 75th anniversary.

This long-delayed genesis gives the building a historical depth: it embodies both the aborted dreams of the interwar period and the endless hopes of the postwar period. It tells of a suspended and reborn time, through the severe brick and remarkable works of art.

The two square towers, some sixty meters high, lend their power to the whole. One of them houses a carillon of 49 bells, the largest in the Nordic region. Its deep, crystal-clear notes rise into the air eighteen times a day, punctuating city life.

This civil cathedral is entered through the north door—the visit is free—with impressive wooden panels carved by Dagfin Werenskiold on either side in the lateral galleries. Sixteen impressive works in high relief, each weighing a ton, ten years in the making, depicting mythical animals, legends, goddesses and gods, vernacular traditions, colorful and graphic—the entire Norwegian folk pantheon on display. “Yggdrasilfrisen” are remarkable.

This civil cathedral is entered through the north door—the visit is free—with impressive wooden panels carved by Dagfin Werenskiold on either side in the lateral galleries. Sixteen impressive works in high relief, each weighing a ton, ten years in the making, depicting mythical animals, legends, goddesses and gods, vernacular traditions, colorful and graphic—the entire Norwegian folk pantheon on display. “Yggdrasilfrisen” are remarkable.

Inside, the City Hall amazes with its colorful frescoes and mosaics. The majestic central hall, the “Rådhushallen,” with its marble floor, is surrounded by murals by Henrik Sørensen and Alf Rolfsen. These frescoes trace Norway’s history, from plowed fields to the workers’ movement, from the Resistance during the Nazi occupation to liberation and reconstruction. Each line, each color, weaves national memory into stone and stucco.

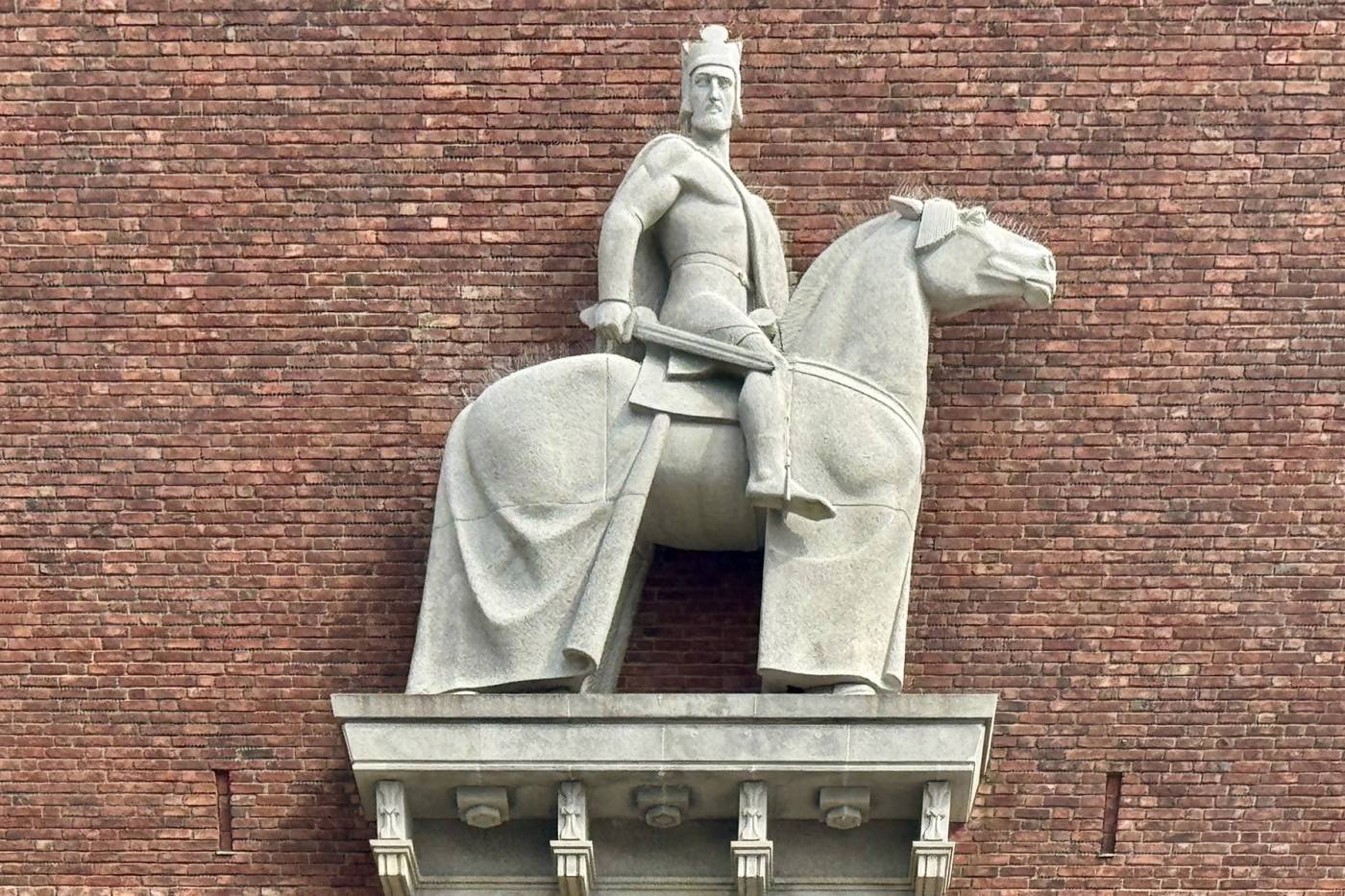

Around the building, guardian figures are also reflected in the sculpted forms. Harald Hardråde rides a horse on the west side, while Saint Hallvard, patron saint of the city, stretches his arms to the sky. In a corner, a sculpture depicts two men and a woman. The pimp, the prostitute, and her client! This surprising representation refers to the brothel district of Oslo, which stood where City Hall now stands.

In front of the steps, six statues by Per Palle Storm embody the craftsmen who constructed the building: carpenter, mason, stonemason, electrician, and laborer—anonymous but deservedly celebrated workers.

In front of the steps, six statues by Per Palle Storm embody the craftsmen who constructed the building: carpenter, mason, stonemason, electrician, and laborer—anonymous but deservedly celebrated workers.

Beyond the formal, City Hall is a place of sociability. Speeches are held there, New Year’s celebrations, weddings are held, the poor are welcomed, and popular festivities are held.

From the chiming tower, a light and familiar melody resonates, perhaps Grieg’s, those brazen notes that speak to the city’s residents as well as to history.

The Rådhus is not content to simply be the city’s administrative center; every year on December 10th, it is the scene of one of the most powerful gestures in world diplomacy: the Nobel Peace Prize award ceremony. In the great hall, beneath the frescoes, the laureate receives his prize in silence in the presence of the royal family and the Prime Minister, who honor this highly symbolic event with their presence. Behind this rigorous and functional façade, an entire ideal—that of democracy, collective ethics, and reconciliation—takes shape in architecture.

Photo: Ken Opprann

Thus, Oslo City Hall is not just an administrative building. It is a manifesto, a sculpted and painted memory, buzzing with bells and hope. It speaks of the nation, not in statues of kings, but in stories of the people, in gestures of peace, in resonant bricks. Functions and symbols intersect there, in solemn simplicity. And from its steps, one can see the sea, proof that architecture can be a beacon.

Brigitte & Jean Jacques Evrard

info@admirable-facades.brussels

Bel article Jean-Jacques, tant par le fond que par la forme, la plume est belle et le contenu donne envie d’en savoir plus, ou de voyager jusque là.

LikeLike